Jim Massey's Fugitives Whiskey

Jim Massey has been an official fugitive since 2016. No, his face isn’t on any wanted posters and he isn’t toting illegal hooch over county lines. “Fugitive sounds like you’re a moonshiner – the old toothless guy in the woods making whiskey,” Jim says with a laugh, “but it’s actually the opposite of that. [The Fugitives were] guys who had a vision of what was important and how we determine who we are as a people.” And they’re the namesake for his artisan Tennessee whiskey.

Specifically, the fugitives to whom Jim refers were a cluster of creatives -- poets, writers, and literary scholars -- centered at Vanderbilt during the 1920s, a group that included some famous names like John Crowe Ransom and Robert Penn Warren and who later morphed into the Southern Agrarians, a literary movement that extolled the virtues of earning one’s living from the soil. Jim comments on the Southern Agrarians most famous tract, the 1930 manifesto I’ll Take My Stand: “the heart of [it] was about honoring the makers. They warned against industrialization and the dehumanization that industrialization causes if we create a consumer society.”

Jim considers Nashville’s present creative community the modern equivalent to the Fugitives and, in that spirit, creates his spirits with their ideals, namely honoring the makers -- the local farmers. “American whiskey has been bulk,” Jim points out. “I’m doing the flipside, doing everything not in a new way, but in an ancient way, highlighting the grain and honoring Tennessee farmers. How can the small farmer thrive? To me, the answer is specialty crops for whiskey.”

It is certainly an idea with precedent in American history. After the Revolutionary War and the migration of settlers to the west of the Appalachians, farmers would distill their corn and wheat and rye into whiskies, the only way to preserve their crops long enough to get them to market which, in our neck of the woods, involved floating whiskey barrels on flatboats all the way down to Natchez or New Orleans. Over the course of time, however, whiskey production morphed into big business rather than the craft of local artisan-farmers. Jim’s mission at Fugitives is to return to all things heirloom, down to the seeds for the grain. “I went through the expense of [growing heirloom varieties] because I’ve got to show that it does make a better whiskey,” Jim says. “When I distilled the first batch, I wanted to see what the corn had to say. And there was so much flavor there.”

It certainly stands to reason. Just as you can discern an heirloom tomato from a mass production tomato through taste alone, so too can you with heirloom corn and rye; they have distinctive flavor profiles. Still, before they can be enjoyed, these heirloom grains must be grown, and, for that, Jim must get local farmers on board. “Farmers are very practical,” Jim observes. “They must ask, ‘ok, if I grow this, what happens if you can’t buy it?’ When you ask them to grow and heirloom grain, without using any chemicals, you’re only getting half the yield and it’s a lot harder work. It’s not for sissies. I’m trying to build a model where they can grow it and I can pay them more per pound so their yield per acre is much greater. The hard part has been working that out.”

Windy Acres Farm, Riverplains Farm, and Teeter Farm and Seed are three of the farms growing heirloom corn such as Hickory Cane and rye for Jim. But getting Tennessee farmers to grow heirloom grains wasn’t the only hurdle Jim had to overcome. There was also the challenge of winning over Tennessee politicians; of convincing them that laws blocking the production of local craft whiskey needed to be changed and getting them to see that whiskey bottles literally contain jobs and are filled to the seal with opportunities for Tennesseans. After all, whiskey throughout history is just good farming. “Everybody wants to think of it as an industrial product,” Jim says, “because American whiskey, for not quite a hundred years, has been mass-produced by just a handful of people. My pitch to the legislators was, ‘this is an agricultural product. You want farmers and the average guy to have a chance? We have an opportunity because Tennessee Whiskey is one of the most famous whiskeys in the world. And yet we don’t make it with Tennessee grain.”

Jim’s efforts have paid off. Our state legislature has now expanded manufacturing of whiskey from the measly three counties it started in and has approved retail package sales and liquor-by-the-drink sales, legislation that should boost demand for the heirloom grains that Tennessee’s farmers supply. Good news for the farmers and certainly good news for whiskey aficionados. But Jim’s not resting anytime soon; he’s still a Fugitive, after all. He’s on the run to keep finding great local corn for his whiskey production.

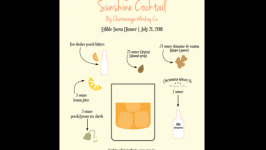

Editor's Note: Jim's whiskey also makes a great cocktail. Check out this one called "The Poet and Farmer."