Hannah's Top Food Reads

Hannah Messinger, local food writer, photographer, stylist and cook, shares her top food books available from Nashville's own Parnassus Books.

All of these titles will be available for purchase on Parnassus' mobile truck, "Peggy" as she tours around Nashville this Spring. You will notice that I have (perhaps woefully) left out some big hitters such as Mark Bittman, Michael Pollan, MFK Fisher, Elizabeth David, and Alton Brown. But that's because this isn't a list of the most important culinary works in the whole world and it's not even a list of my favorite. No, these are the books that made me the cook and writer I am today, the ones I can consider "formative." They are dear to me and I hope that once you read them, they will be dear to you, too. Drop me a note and tell me what you think of them at HMMessinger@gmail.com.

An Everlasting Meal: Cooking with Economy and Grace. This was really the first book that changed my life in so far as it drastically changed the way I cook. It is a modern version of MFK Fisher's How to Cook a Wolf and it helped me add both wisdom and efficiency to my kitchen. Adler writes, "Meals' ingredients must be allowed to topple into one another like dominos. Broccoli stems, their florets perfectly boiled in salty water, must be simmered with olive oil and eaten with shaved Parmesan on toast; their leftover cooking liquid kept for the base for soup, studded with other vegetables, drizzled with good olive oil, with the rind of the Parmesan added for heartiness. This continuity is the heart and soul of cooking." She also includes cures for nearly every kitchen mishap, from over salting soup to overcooking meat. I have been cooking nearly every day for a decade and am far from immune to kitchen disasters; I still turn to this book on a regular basis to save my ass and my dinner.

Ratio. I'm not going to lie to you or sugar coat this: Ratio is by far the dullest book on this list, but in many ways it's also the most important. It taught me the building blocks of cooking, the basics I needed to implement the gift of efficiency I received from An Everlasting Meal. It made me a die hard believer in the kitchen scale and a more versatile cook ten times over. As Ruhlman puts it, "Only when we know good can we begin to inch up from good to excellent." Many of the recipes that we know and love, he says, do not help us become excellent, but hold us back by chaining us to them. That's a hard pill to swallow, but once it goes down, its healing powers are magnificent.

Supper of the Lamb. Normally I don't recommend books written by Episcopal priests. Normally I don't read books written by Episcopal priests! But man, Robert Farrar Capon is the exception that proves the rule. The subject of this work is the under appreciated and often over looked aspect spirituality in cooking, an expansive topic that Capon covers with eloquent ease. His thoughtful words regarding the physical and metaphysical world miraculously eradicated many of my fears, both in the kitchen and elsewhere: "A calorie is not a thing; it is a measurement. In itself it does not exist. It is simply a way of specifying a particular property of things, namely, how much heat they give off when burned. Only things, you see, are capable of being eaten or burned, loved or loathed; no one ever got his teeth into a calorie. In fact, if you think carefully about it, you will realize that no measurement exists as such...How sad, then, to see real beings...living their lives in abject terror of things that do not even go bump in the night."

Seasons. Growing up, much as I loved Martha Stewart, I couldn't help but wish that she was a little more chill, her recipes more down-to-earth, and her content more focused on actual cooking than on magazine and ad sales. Then I grew up and learned that this version of Martha does exist out in the world; her name is Donna Hay and she's an Australian angel. Her book "Seasons" is a compilation of popular recipes from the magazine and it is nothing short of phenomenal. The recipes themselves, unencumbered by story, are simple yet innovative and the photography and styling are focused on the food, and not, as many cookbooks are today, on the props. Ingredients are listed by weight, making little room for error. I'm especially fond of the non-traditional recipe for Greek salad, which is centered around a large hunk of pan-fried feta.

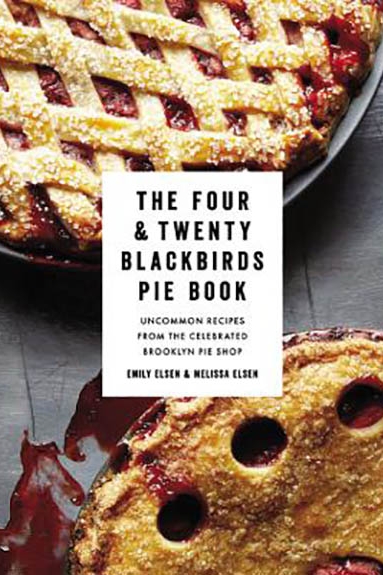

The Four and Twenty Blackbirds Pie Book: If you only learn to make one dessert, learn to make pie and to make it well. First of all, everyone likes pie. I dare you to name one person who doesn't like one type of pie. Second, let me tell say: once I conquered pie in all its various forms, hardly any kitchen task seemed daunting. Croquembouche? Okay. Macarons? No problem. Creme anglaise? Childs play! Simple though it may seem, pie making is an art that requires diligence, patience and practice- and the green cook seldom has all three. I know I didn't. The Elsen sisters were and are my trusted allies on the path to pie victory. No, scratch that; they were are are my shamans on the path to pie enlightenment.

Mad Farmer Poems. There's a poetry to the way anything grows, whether it be a idea or a tree or a human child, and one of the most poetic things in the whole world is the growth of our own sustenance, a foundation of cooking deeper even than ratios. And no one explains this sentiment better than Wendell Berry. I don't remember how or when I first read this book, only that I boo-hooed through the entire thing, as I still do when I lay eyes on its pages. I read it often and with each passing word, my faith in the goodness of this world is restored. Berry's poetic tenderness made me appreciate and trust him in a whole and complete way as I went on to read his more scientific works on the subject of farming, such as The Gift of Good Land, which is currently on my nightstand.

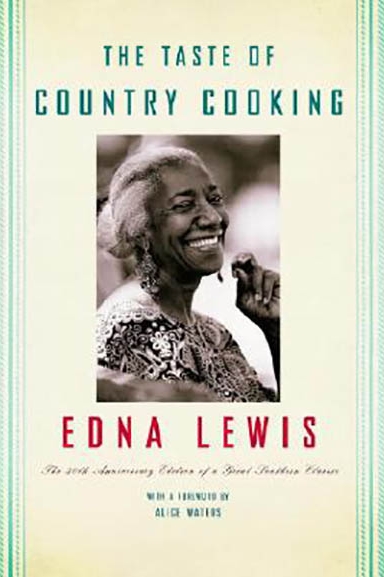

Taste of Country Cooking. Edna Lewis is a national treasure and anyone who says otherwise is a liar and a scoundrel. Taste of Country Cooking is a heartwarming plate full of nostalgia, the type of book that I think we all wish to write towards the end of our lives, to look back and remember what made us us and pass that thing, whatever it may be, down to the next generation. For Lewis, that thing was cooking, and by extension, the farming and rituals and bonds that fueled her family's kitchen in Freetown, Virginia. Her memories are a fascinating slice of American history and more importantly, they are, she writes, a time and place "so very dear to her heart."

Provence, 1970. This entire book feels like a big, juicy piece of gossip and well, it kind of is. Luke Barr, MFK Fisher's great-nephew, had the wildly great fortune of being privy to her private diaries and letters, her most secret thoughts and desires, which she recorded during a pivotal winter spent in France with Julia Child, James Beard, Richard Olney, and Simone Beck. It is a historical portrait of these culinary behemoths alongside insights on how their time together influenced the way we eat now. I only read it last year, but it sparked in me a fascination with culinary history, which recently lead me to the work of Michael W. Twitty, author of the blog Afroculinaria and of the upcoming The Cooking Gene, a book that will undoubtedly land itself permanently on this list the moment I close the back cover.