Near Beer: Taking the Farm-to-Table Movement to Your Glass

I'm no snob when it comes to beer. I’ve bought plenty of light beer, dark beer, whatever-is-cheapest beer. It’s not that my taste buds aren’t experimental, it’s just about the economics and ease. But I find myself stumbling over the idea that what I'm imbibing has no relation to the space around me. I wonder, Where do the ingredients in this drink come from?

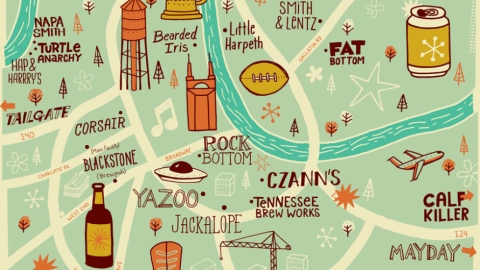

Farm to Tap, a program whose aim is to get Tennessee products into Tennessee drinks, certainly alleviates my fears. It is a group created by the Tennessee Department of Agriculture and the Tennessee Craft Brewers Guild (TCBG), a nonprofit representing more than 70 Tennessee craft breweries. Inspired by the “Agriculture and Commerce” state motto, Farm to Tap hosts networking events for farmers and brewers, educates farmers and brewers on how they can collaborate and encourages consumers to buy Tennessee beer made with Tennessee ingredients.

“If you think about the farm-to-table movement, that’s what we’re trying to create but for beer,” says Sharon Cheek, executive director of the TCBG. “I’ve been a craft beer fan for a long time, but I never really thought about how beer is an agricultural product. For me, a big piece of Farm to Tap is awareness that there’s a farm in your beer.”

Kyle Hensley, a business development consultant at the Tennessee Department of Agriculture, says when Governor Bill Lee’s administration took office, they looked at industries that could be supported further. Hensley was tasked with working with the alcohol industry and set out to connect brewers and farmers. “It’s a ‘what came first, the chicken or the egg’ thing,” Hensley says. “The farmers can’t grow for the brewers unless the brewers are willing to make a commitment to buy. The brewers don’t feel comfortable committing to buying something from someone they don’t know. We hope Farm to Tap helps bridge that gap.”

Let’s go back in time. Beer, the result of fermented grain, is the oldest and most consumed alcoholic drink in the world, with archaeological evidence of fermentation dating back 15,000 years (just before the Agricultural Revolution). But the first proof of intentionally produced barley beer dates back 7,000 years to present-day Iran. 6,000-year- old Sumerian and 5,000-year-old Chinese artifacts show they drank beer, too. Neolithic Europeans probably brewed beer at the same time as the Chinese, but fast-forward to the Industrial Revolution when continental Europe, Great Britain and the U.S. employed machinery, factories and other production advancements to grow businesses, populations and trade. Plus, more beer.

Thousands of breweries existed in the United States before Prohibition, and they made beers that many of us today would find too strong. But when alcohol became scarce, bootleggers watered down drinks to increase profits, creating a trend of highly advertised weak beer that continues today. Then breweries faced consolidation from larger firms who bought out competitors.

Today, craft breweries amount to just a quarter of the $100 billion U.S. beer market, despite 9,000 craft breweries and under 150 non-craft ones.

When it comes to ingredients, it is frequently financially easier to ship grain from a large company elsewhere than it is to buy from a local farmer, since prices may be higher if their output is lower.

“Consumers are more aware today of their food supply chain than they have been in a long time,” Hensley says. “It wasn’t that long ago when everything was local. [But today] we’re part of a global economy, and it’s a good thing in a lot of ways, but we’ve gotten away from knowing where our food comes from, and you can see the consumer drive for ‘I want to know.’”

Cory Willis of Hillsboro, Tennessee’s Willis Farms, which specializes in cattle and row crop cultivation, began growing barley for fun. But when he learned the farm could handle more barley, he looked for potential customers. His first customer was Carolina Malt House and he is now partnered with Manchester, Tennessee’s Common John Brewing Company and Nashville’s Tennessee Brew Works.

“One of the reasons barley worked for us is because it was similar enough to growing wheat. You treat it basically the same and you can make a little more money. But it’s fun to go somewhere that is using a product you grew and to sit beside somebody who’s greatly enjoying something you had an integral part in making. Feeding chickens and growing soybeans for industrial processes is necessary to what we do, but for me, barley is way more fun!”

Nate Underwood of Harding House Brewing Co., a leader in the farm-to-tap movement, adds terroir—the natural environment in which a beverage is produced—to his products. “Every beer that we brew has a local product in it,” he says. “We use 100 percent locally grown grain in every single beer. We use heirloom varieties of local corn; if you’re growing different varieties of corn, we want to know. We want to give people a real taste of Tennessee and brew beer that has a true sense of place.” Clarksville, Tennessee’s Teeter Farm & Seed Co., Three Daughters Farm (just north of Nashville) and the Nashville Food Project all have partnerships with Harding House.

These are the kinds of relationships Farm to Tap wants to create and amplify. They will announce a cost sharing program later this year for farmers and brewers to buy equipment to more easily process Tennessee products. They also created an ale trail, a “passport” program to check in at over 60 Tennessee breweries. “Whether you’re a tourist or a resident, the more you visit these breweries around the state, the more you're supporting local agriculture,” says Cheek.

Beer brings people together just like it did in Mesopotamia. “It’s one thing to bring in jobs, but people are not robots. They need something to do outside of working hours, and a brewery can provide a phenomenal community center in rural and urban areas,” says Hensley.

What other ingredients would Underwood like to use? “I would love to brew with cherries. Hops can grow in Tennessee, and I would love to see oats grown in the state.”

The potential for bountiful relationships between farmers and craft brewers, or any food and drink producers, is exciting and exemplifies the underlying connections we share as Tennesseans. It’s up to us who live here to build the community. Farm to Tap is doing their part by building relationships. As a customer, I can do mine by paying attention to what’s in my beer. I’m happy to help my neighbor by having a draft!

For more information on the Farm to Tap initiative, check out farmtotap.org. To find Tennessee-grown products, go to picktnproducts.org.